College Blog

Informed consent is an essential part of all physiotherapy care.

But what happens when a patient can’t make decisions about their health care? That’s where substitute decision-makers come in.

A substitute decision-maker is a person who is authorized to make health care decisions on someone’s behalf when they are not mentally capable of making those decisions themselves. This could be for a short time (for example, after an accident) or a long time (for example, due to advanced dementia).

Ontario law lays out a hierarchy of who can act as a substitute decision-maker.

In this blog post, we’ll go over key things physiotherapists should know about substitute decision-makers and how to prioritize communication and patient autonomy when having important conversations about consent.

Start with the Patient

Many people living in long-term care homes have named attorneys for personal care. That doesn’t mean you should skip talking to the patient and go directly to the attorney for personal care as the substitute decision-maker.

Similarly, don’t assume the person who brought a patient to their appointment is their substitute decision-maker.

Start any assessment or treatment as you normally would, by talking to the patient.

Assessing Capacity

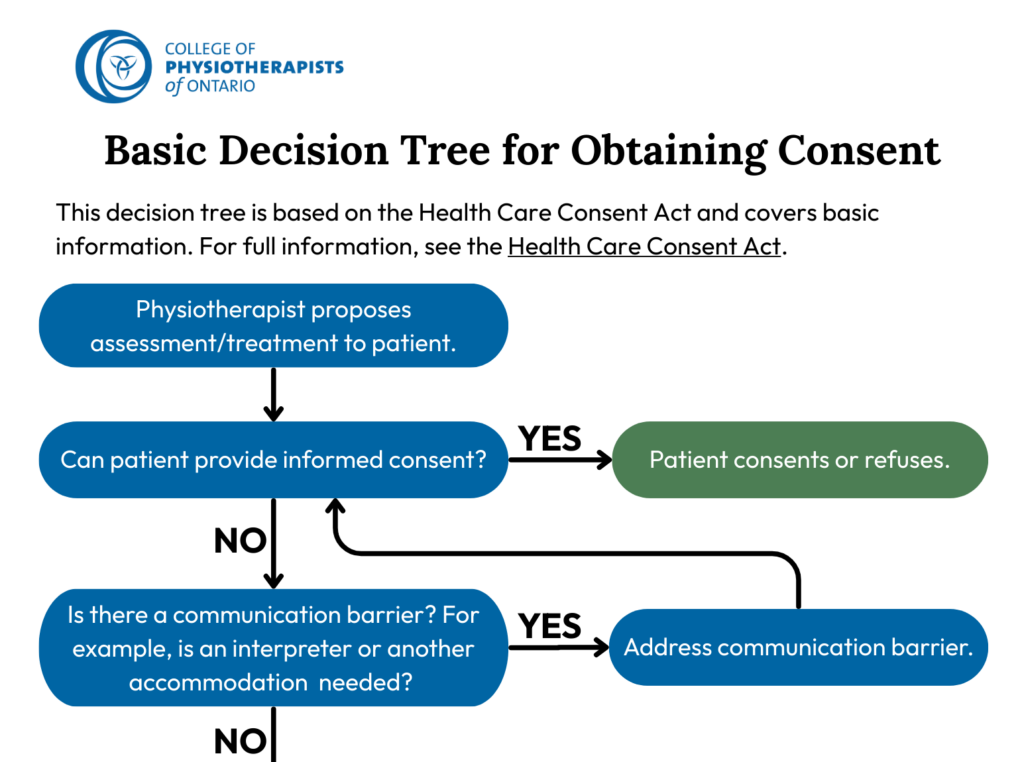

Physiotherapists aren’t responsible for carrying out formal capacity assessments – that’s something done by other medical professionals. But physiotherapists do need to use their clinical judgment in the moment to determine if a patient can provide informed consent.

Informed consent means the patient understands what you’re planning to do – whether it’s an assessment or treatment – and agrees to it. This includes understanding the benefits, risks, potential side effects, alternative courses of action, and the possible consequences of not having the treatment.

So how can you tell if a patient understands what you’re talking about?

Here are some signs:

- The patient asks relevant questions

- They can paraphrase what you explained

- They’re following the conversation

Misconceptions to avoid:

- Assuming because the patient can follow simple instructions, for example lifting their arm, they have given you informed consent

- Assuming because the patient signed a consent form, they have given you informed consent

- Assuming nodding, without meaningful verbal interaction, means that the patient understands what you are saying and is giving you informed consent

What If There’s a Communication Barrier?

Sometimes, a patient may not be able to understand you – not because they lack capacity, but because of a language or accessibility barrier. For example:

- If you don’t speak the same language as the patient, you may need an interpreter

- If the patient is deaf or has hearing loss, you may need a sign language interpreter or a family member who can help bridge the communication gap

The need to make accommodations doesn’t mean the patient lacks capacity to consent. It just means you need to take steps to ensure they can fully understand you.

When Capacity is in Question

If the patient appears disoriented, confused or otherwise unable to understand the information provided, it may be time to involve their substitute decision-maker.

In Ontario, everyone automatically has a substitute decision-maker. The Health Care Consent Act lays out who this would be. For most people, their substitute decision-maker will be their closest family member. This happens automatically and doesn’t require paperwork.

Some people will have a legally appointed substitute decision-maker. For example, a patient’s automatic substitute decision-maker might be their spouse. But the patient could choose to appoint their daughter as their attorney for personal care. In this case, their daughter would become their substitute decision-maker.

Here is the hierarchy of substitute decision-makers:

- Guardian of the person

- Attorney for personal care

- Representative appointed by the Consent and Capacity Board

- Spouse or partner

- Child, parent or a children’s aid society or other person who is lawfully entitled to give or refuse consent in place of the parent

- Parent who has only a right of access

- Brother or sister

- Any other relative (related by blood, marriage or adoption)

- Public Guardian and Trustee

Some people will have more than one substitute decision-maker. This happens when there are multiple people at the highest level on the list – for example, a child with two parents or someone with several siblings. In these cases, the substitute decision-makers share decision-making authority.

If you’re not sure who a patient’s substitute decision-maker is, you can ask the patient, review referral documents or call the patient’s family doctor.

Consent is Still Ongoing

Even when a substitute decision-maker is involved, it’s important to continue engaging with the patient. They may not be able to make big decisions about their care, but they can still make choices about what happens during their appointment.

For example, you might ask:

- Would you prefer to sit on the bed or in a chair?

- Do you want to walk inside or outside today?

Care should always be patient-centered – regardless of a person’s level of capacity. That includes having ongoing conversations about consent with the patient and their decision-makers.

Resources

Basic Decision Tree for Obtaining Consent

College Consent Resource

Considerations for Obtaining Consent When Custody Is in Question

Health Care Consent Act

Share Your Thoughts